Interview - Memorable Words from Aphasia’s Marielle Dalpe

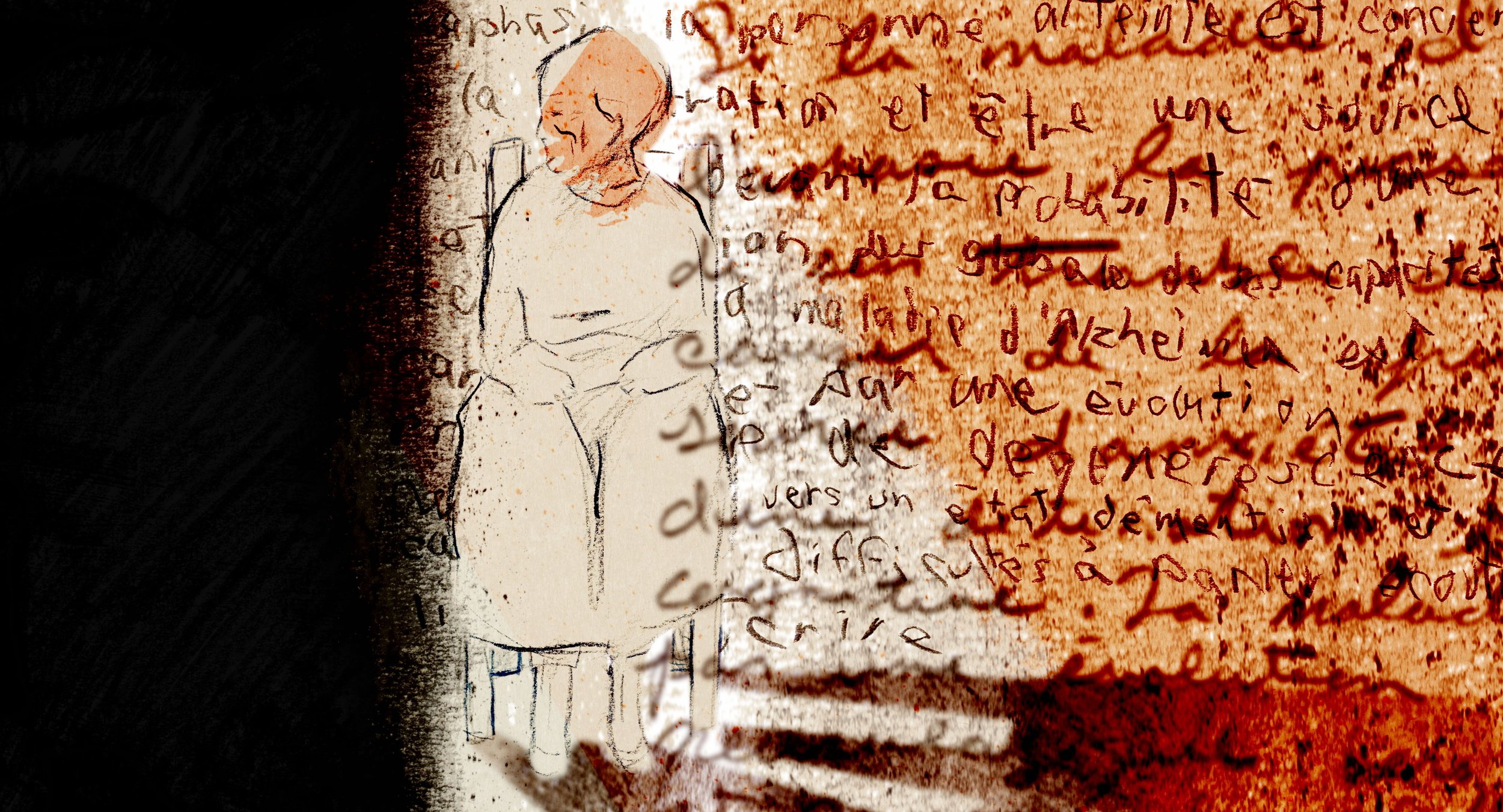

Courtesy: NFB

The following interview was transcribed and edited for length and clarity within the context of the editor’s feature piece.

Propelled by a jarring, lyrical aesthetic, Aphasia stands as a poignant testament to the artistic exploration of the human condition. In this striking and unsettling debut professional animated short by Marielle Dalpé, viewers are inexorably drawn into a disconcerting sensory experience. The film delves into the heart of aphasia, a devastating neurocognitive condition that progressively erodes the fundamental ability to speak and understand words, especially afflicting individuals with Alzheimer's disease.

Aphasia, as portrayed in Dalpé's work, is not merely an abstract concept; it is a jolting experience that forces the audience to confront the harsh reality of a disease that impacts a staggering number of lives. According to recent statistics, aphasia affects approximately 2 million people in the United States alone. This statistic serves as a stark reminder of the widespread reach of this neurocognitive condition, highlighting its significant impact on individuals and their families.

Marielle Dalpé's artistic endeavour serves as a powerful vehicle for raising awareness about aphasia, transcending the boundaries of traditional storytelling to immerse the audience in the emotional and psychological turmoil experienced by those grappling with this condition. Through her lens, the viewer is not only captivated but also educated about the profound challenges faced by individuals battling aphasia.

First of all, how was Toronto? How was TIFF?

Marielle Dalpe: I'm good. Toronto was great. I mean, yeah, it was a bit surreal to be at TIFF. You know, first professional film, first premiere. So it was great. It was amazing. Such a good way of starting.

Why don't we chat a little bit about Aphasia. When I was watching it, I was really struck by it. I think, in the media, oftentimes when we see depictions of something like Alzheimer's, it focuses on depicting confusion and so on, but it's tends to feel like we're outside looking in. And so we get like the graceful distance of seeing them confused, but not internal confusion of being in that moment. And obviously, you decided to go a different route. I was wondering if you could speak a little bit about what you wanted to say with the short?

MD: Yeah. Well, you kind of got it, I wanted to put the the viewers in the head of somebody that was losing their language, capabilities and having Alzheimer's, I wanted to take another route. Like, obviously, I've seen a bunch of film and animated film on Alzheimer's disease. And I wanted to approach it in a different way, talking about aphasia, but also, I wanted to depict Alzheimer in a more aggressive and violent way. I have a lot of respect for all these other films, because they helped me through my grief, and grieving through my grandmother who had Alzheimer's. So they were great for me, but there was this part where I was like, but it's such a violent disease. And I thought it yeah, I just wanted to like show that, you know, yeah,

Right. I think sometimes, because we want to be generous with friends who are going through it, or family members, or whomever it may be, we want to portray it in a way that's respectful to them. But I think, this acknowledgement of how violent and jarring it is, really exemplifies a little bit more about what people are going through.

MD: Yeah, I had a lot of experience because we would accompany my grandmother through all the different stages, and therefore you meet other people that that are dealing with loved ones that are at different stages of Alzheimer's disease. I remember so many encounters where we were all tired, hurt. And then, we just wanted to, like communicate like to be in a community to like, talk about it. But at the same time, it's so personal. You don't want to share too much with strangers. But I just remembered, it was hard for everybody. And I think there's there's something cathartic about showing that, you know, in some way.

When I was watching it, was it difficult to kind of land on the sense of confusion, or, you know, like levels of how jarring this that you wanted to, to portray? Because I think also at some point, you could maybe take it too far. And then it's like, difficult to see that juxtaposition, right? Like, was it difficult to strike that balance?

MD: Um, yeah, well, I mean, it took a lot of work to do it. The first idea that made my film was the, the, at the time I call the glitches but it's the idea of the narration being interrupted by aggressive sound. So I knew I wanted to take it in a confusion away and from the get-go. But it was it was hard to navigate between the information that I wanted to tell people and then what was okay to leave in the confusion and to be completely lost. And I was very aware of the, the audience and I was also, I was okay, if you the audience didn't get everything, you know, like theirs wanted it to be an experience for for them and therefore, I was always negotiating with as long as people learn in about the right area of what I want to say, I'm okay I want them to feel you know, it's surreal, like feeling.

Yeah. It's interesting to me because when I watched it, there are so many moments when there's a lot that's going on screen, but it's again meant to be fast and jarring. And my instinct was almost like, I want to pause this and capture everything in that moment. But doing thatkind of felt almost like betraying like, the sense of like, how ephemeral it is, right? Like it comes in, it comes out. And like, maybe that's how it should be. Do you think about the way that people will take in your art or interact with it?

MD: People can do what they want, I really like doing bad metaphors, and the one that I like to use is like, you know, like you're out of a football field. And you can have people in the bleachers, you can have people playing the game, you can have, like, people just playing tag around the polls, like, I'm happy with all of that, as long as they're not in a tennis court, like on the other side. So I leave it, I'm very comfortable to leave a lot of space for my audience to feel if they think about the Alzheimer's more than the aphasia I'm okay, if they think more of death. You know, like, there's, there's a big space there and I'm happy that I make you feel stuff. And that you learned a little bit.

Trust me, it was very effective. I wanted to ask you a little bit about too, it's like aphasia is just one of the symptoms that kind of show up as things progressed. And it's interesting to me because, like sound and like language are so important. You know, like, obviously, it's not directly related, but like, we find our balance and like our focus to our ears. And then just like the way that language is so important to communicating, like being tethered to your community and so on. I was just curious, as someone whose job is communicating in a way, do you think that somehow influenced the reason on why you pinpointed like this part of Alzheimer's to explore?

MD: It comes more from a personal story, like my grandmother had Alzheimer's. And she didn't have the classic forgetting her loved ones around her things. She remembered us up until her death. But she was a woman that read a lot, went to the theater and aphasia was one of the first and main thing that happened to her. So once she passed away, and I was doing some research, just to help me, like, figure out what, what has happened, I stumbled upon aphasia, and it was like, a light of understanding. And I thought I was in the dark, so why not talk about this aspect of it, maybe more people would like, our living that. And it's interesting, because even though my film is about aphasia, and Alzheimer's, I've had so many people that have that have suffered, at one point through their life from aphasia come to me and say, like, Oh, your film really, really spoke to me, you were able to like, Put your finger on something that I hadn't seen before. So there's that. And I find that language is just a very interesting topic. As a bilingual in Canada, I, you know, it's something that I think a lot about. So it was just all these things that made me want to approach that subject.

I think you described your technique for this short as animated textures. I'm just wondering if you could maybe expand on that a little bit for people that may not be as familiar with animation, like, what does that mean?

MD: It's a technique that's called under camera. So you have a camera on top, like, facing straight down onto a table, and they would have like, papers, all kinds of stuff. And then the animated textures would be like paint that I would put on my page and shuffle around and take a picture and then shuffle around again, take a picture, and then I would create what we call the image sequence. That's kind of like textures that are animated. And I would do that for different kinds of things. Paint, ink, like crayons, any kind of that have that kind of material, because it was important for me to have, that my film was made with real, real things, you know, just to ground us a bit more into what was happening on screen. My film is about humans. So, you know, having more things that just like, puts us, so that's why I went through all this, like, more work, art, material things that it was important for me to do that. And so yeah, it was just like, and I would also like, sometimes just do like blobs of, of paint. And then after that in the computer, I would come and select them and then create animation. With the computer with all the pictures that I had taken. It was a little bit of live animation and computer.

That must have been so so much work.

MD: It was, but I really enjoy that. That's why I did it, I really enjoy it. And I really let myself like, there was like two steps, the under camera part and then all the computer things. So my textures like, I put like textures and textures and textures, I superposed them. And it was just like to create more depth. It was fun to experiment in that way.

Those two kinds of streams of creation, over the camera looking down and the computer part, do they happen at the same time, like you have to keep on going back and adjusting things? Or is it like you capture everything at once and then you go to the computer and then you start working there.

MD: Um, I did a little bit of both, at first sent in more under camera, but then I would always go to the computer to see if it was working. So it was a back and forth most of the time. But I did leave a lot of space in my production towards the end for just the computer so that I could make a film that was like a uniform. And then so when that was happening, then it would sometimes bring new ideas. And then I would go back onto camera and do a little bit more. Bring it back. So it was like there were two blocks, but at the same time there was always this back and forth.

I was curious about your journey to getting here.

MD: Oh, yeah. I'm from Montreal, I come from a family of theater people. So I have the arts just in my family. And, you know, even primary and high school was like in more of a alternative art school, then then we have CEGEP in Quebec. So that was the art program. And I discovered sculpture during CEGEP. So I went to school in Halifax, in their art school to study sculpture. And that's where I discovered animation. So I packed my bag went back to Montreal and studied at Concordia. They have a film school there that has an animation program. Since then, well, I you know, I graduated and I've been working. I tried to be a freelancer, which brought me to do more contracts in well in theater, concerts, like video mapping. So things that were like in the onscreen more like, an big area in different ways. YBut where I could have like a little bit more of a, a hand of like, my own art in it in those projects.

Going back to the beginning when we're talking about about TIFF, you know, I know this has been like an official selection for a lot of other festivals to like, as somebody that's creating these shorts, like, what is the film festival part part of this equation? Like how does it work for you like because it's something that you know, it's part of A process to be able to get your work seen isn't something that just, you know, recognition matters. Like, what's the how to film festivals play into this?

MD: Oh, yeah, they have a very important part. In short animated films. They mostly live in festival settings. So you finish your film, and you have about a year or two, where you do a bunch of festival and it fits going well, that's, that's great. But, and that's where most people will see your film. And then it will go on the internet. But you know, like, people might not be inclined to go see short animated films like they, once it's online, there's less publicity for it. So it's really the festivals are really where like, it's your chance for your phone to, to be seen. It's important for I don't know how it is for other like for live action, short films, but in animation, it's definitely a crucial, crucial part of the film's life.

How did your relationship with the National Film Board of Canada start? Was it from the beginning of Aphasia?

MD: It was a long, long time, into the process. Aphasia started as an idea and then I started to do my research. And I knew I wanted to make a film about it. So I tried different ways and things, and it was not quite there. And then in 2019, I was in a meeting for a contract and the presentation, there was a glitch, and I went, Oh my God, that's my film. So that's when the film became the film. And so I decided to do it independently, and try to get financing for it. And that's where I also, that's when I also recording the voice, the French actress voice was before the NFB got into into the mix. And then, nothing panned out for financing. And then the pandemic happened. And that was a little bit like off, you know, I was a bit done, it had been a few years of wanting to make that film. And, but I couldn't put it a like on the on the shelf. If I hadn't tried the NFB, it was the only place that was left. And I was like, if if I don't propose my film to them, I'd be I'll be mad at myself for not doing it, you know? So I put up a really good proposal and send it and then and then they they accepted it. And here I am.

Amazing. I mean, just out of curiosity, like what what did it feel like when you were done and this idea of being with you for so long? And I would imagine it also took a very it's a very laborious to put all this together like once you were like this is the final version. What does that feel like?

MD: It's amazing. It's also like you're very tired by the end. But it was great. I was so happy I think it's more because it's such a rush at towards the end I think actually it was this week when it was finally presented that it was amazing because I had been wanting for people to see it as I said the the audience is such an important part of how I created this film. It was so nice for it to be finally seen and that was when you know the realization that I made the film, that it's the film that I've been wanting to make, it's just a great feeling you know?

I would assume that that you're you're really has seen it I'm curious if you want to share you don't have to but how did they react to seeing it? The public, your family, your family everything?

MD: Oh my family they they loved it. They were like they didn't expect that I think they were really touch I think they were really touched it in expect that. That kind of rawness from from the film and yeah, no, no, it was uh, yeah. Yeah.

I mean, it's always interesting. I'm a big fan of comic books. And sometimes people are like you like, how does it compare to books and it's just like it's a different language all or sometimes, right? So it's like, especially for something like the animated film that you've done and, and other portrayals of Alzheimer's, it's just so different, like, so unique. So So I think it's like such a such an interesting perspective on it. I know that if it has been like, I have my list here artificial selection for Ottawa international Animation Festival, Atlantic International Film Festival, Montreal and London it is so I'm guessing on what is next. But you know, kind of after this, like, what do you envision the future of this film? It will be I know, you didn't mention like maybe putting it on the internet once the festival circuit is done. But is that something that you think about already? Kind of like, Where does this live next after that festival circuit?

MD: Yeah, so hopefully, we'll have a nice festival run. And then we're hoping that maybe we'll be able to, like, reach out to, to some. I don't know exactly like how to say it, but the community's like, towards like, people that deals with Alzheimer's,.

And I mean, maybe it's too early to think about this, especially so much effort and time put into this one. But what's next for you after after this? Like, do you have ideas already percolating that you're thinking about or too early to start thinking about beyond beyond the next couple of years,

MD: I like to have always, lots of projects at different levels of things. So I actually just finished the production of another experimental film. And I'm studying post production, this all and it was a project I did a film on on the train between Toronto and Vancouver and back. So in the in the two weeks of that travel, I did the whole the whole film like filming, editing, compositing, the sound recording and all sound conception and all of that just in that like, period in the train, like being being influenced directly by the traveling and just like, trying to like, Yeah, but so that's the that's the one that I'm working on right now. And that's in the, in the finishing stages. And I also have a graphic novel that I'm trying like now that the big the big aphasia project is done trying to like, go into this other like graphic novel project that is close to my heart.

Layered Butter is a community dedicated to the art inspired by film. Through essays, interviews, and artwork, our mission is to celebrate and champion what we love about the movies. If you like our work, please considering subscribing to our Patreon, purchasing a digital issue, or pre-ordering a physical issue through our store. With your help, we'll be able to grow this community and support the artists and writers who make Layered Butter possible.