Everybody Don’t Need a Stuntman

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood - Pete Lloyd

“Now, if you think you’re seeing double, don’t adjust your television sets because, well, in a way, you are.” On the set of the fictional Western television program Bounty Law, a promo host introduces both his fictional small screen audience and the viewer to the two ruggedly handsome cowboy types sitting beside one another. So begins Quentin Tarantino’s magnum opus and his sprawling love letter to Los Angeles circa 1969, Once Upon A Time In Hollywood.

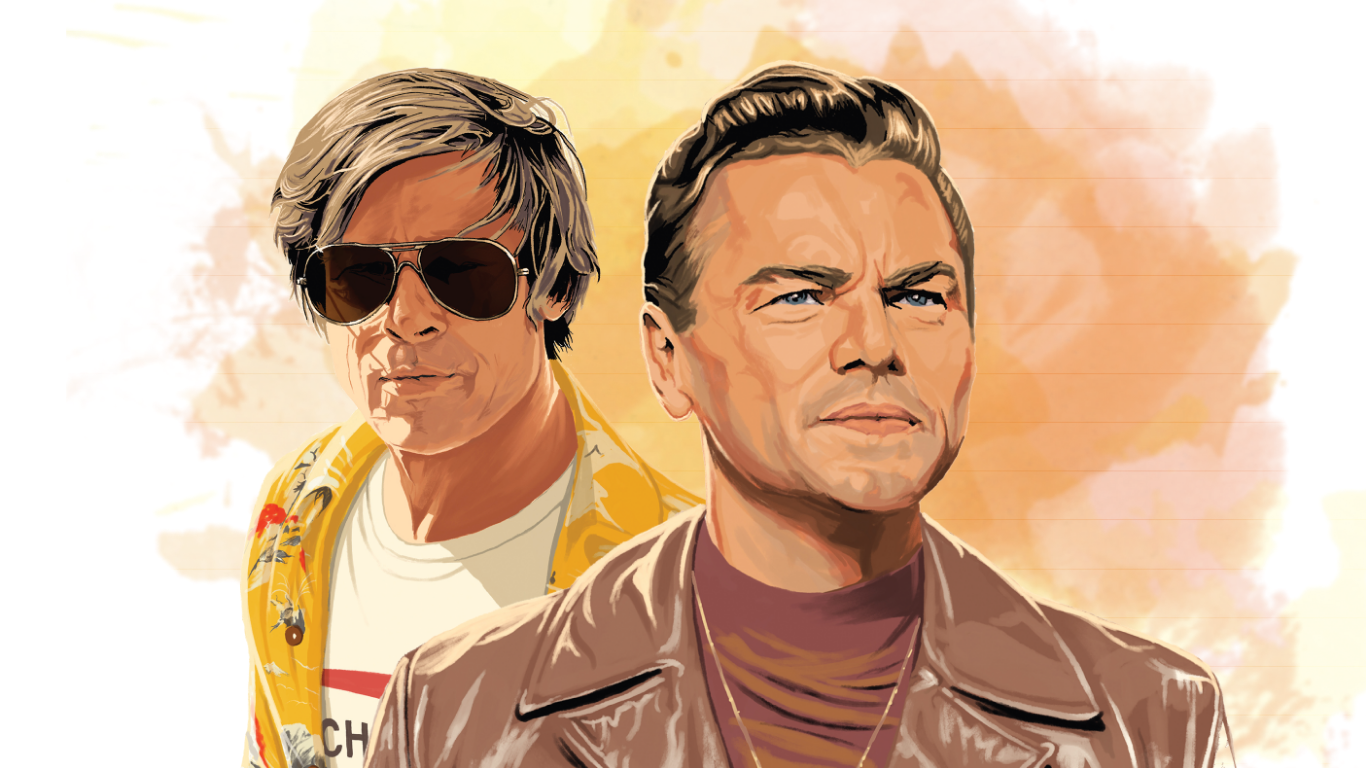

The pair in question is actor Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) and stuntman Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) and together they form the role of Jake Cahill, the protagonist of Bounty Law. Doubles though they may appear, the two men occupy distinctly separate roles in Hollywood, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, the truth of their many divisions and dualities is more complicated than what can be distilled into their introduction. Over the course of three days, as Rick and Cliff watch their friendship, careers, and lives ebb and flow, Tarantino grapples with what it means to witness the dying light of a golden era and whether it truly matters if that witnessing isn’t done alone.

While this central duo weaves their way through Hollywood, there’s a growing counter-culture surging at the periphery. The inheritors of Los Angeles primarily exist in two forms: the vulgar hippies and the fresh-faced new pool of talent. In the first category, there are the scruffy-looking flower children who wander through the city barefoot, yelling at cops and hitchhiking to and fro.

Then there’s Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie), a burgeoning A-lister who shines like a beacon of light at parties and delights in watching her career begin to take off. She isn’t one of the hippies, but she’s accommodating and understanding, she happily gives a young hitchhiker a ride and after striking up a conversation with her passenger, wishes her well on her journey. Sharon, unlike Rick, isn’t clinging to the ways of Old Hollywood, she’s embracing everything that comes with change, whether it’s befriending the more free-thinking members of her generation or making a name for herself in Valley of the Dolls, a controversial film that the Motion Picture Production Code would have demolished a decade prior.

While Sharon is thriving in New Hollywood, Rick has all the emotional fortitude of a child watching someone else play with their favorite toy. His career hasn’t panned out the way he expected in the years since Bounty Law ended. Although he isn’t ready to throw in the towel just yet, he’s gripped by the fear that maybe this is it for him. Maybe he no longer belongs. Maybe his peak was the years spent as a TV cowboy. Maybe he’s doomed to Spaghetti Westerns and guest-starring roles on the small screen. It’s not a bad career, it’s certainly more than many aspiring actors achieve, but the encroaching possibility that he isn’t destined for glory is clearly wearing on Rick in the twilight of the 1960s.

Helping him deal with this is the much more laid back Cliff. While Rick fights back tears in the passenger seat, Cliff — his stuntman, driver, therapist, handyman, and best friend— is the one to remind Rick that going to Italy and starring in movies isn’t a fate worse than death. He’s the one who assures Rick of his talent and ability, gives the frazzled actor a shoulder to cry on, and takes care of duties around his house so Rick can focus his attention elsewhere.

While the two have their similarities, Cliff is comfortable to live outside of the limelight. In contrast to Rick’s home in the Hollywood Hills, Cliff and his own companion, a pit bull named Brandy, live in the Valley, occupying a trailer parked behind a drive-in theater. Rather fittingly, Cliff quite literally exists in the shadow of the silver screen, comfortably adjacent to Rick’s world, but never in the spotlight himself.

On the second day of the film’s narrative, while Cliff ambles through the city during the hours that Rick is at work, he gives a young hitchhiking hippie, Pussycat (Margaret Qualley) a ride home to her friends. As fate would have it, Pussycat and her “friends” are the Manson family, who live in the rundown remnants of Spahn Movie Ranch. The mini Western main street used to be the Bounty Law set. Now, dogs roam free and every square inch is covered by sand and dust. It’s been nearly a decade since Cliff worked as a stuntman there, but it might as well have been an entire lifetime ago.

As Cliff discovers, the owner and proprietor, George Spahn (Bruce Dern), has given the Manson family free run of the place. George doesn’t remember Cliff or Rick; he scarcely remembers that there ever was a cowboy show that spent several years filming on his property. George is old, and blind, and couldn’t seem to care less what goes on. “Everyone don’t need a stuntman,” George tells Cliff — his way of saying he’d rather be left alone.

The world of Hollywood that brought Rick and Cliff together in the first place is no more. Times are changing, or rather, they have changed, forcing the stubborn actor and his far more amenable partner to adapt.

With Cliff in tow, Rick makes his changes. He goes to Rome, films a handful of movies, and returns six months later with an Italian wife on his arm and four more titles on his resume. It should be a marker of success, but something’s shifted. As he explains to Cliff, touching down in Los Angeles again means a parting for the friends. Rick has a wife to support, and that means taking Cliff off the payroll.

The transactional nature of Rick supporting Cliff should make the dissolution of their friendship easier, but it doesn’t. As the omniscient voice of Kurt Russell narrates, “When you come to the end of the line with a buddy who is more than a brother and a little less than a wife,” there’s only one way to truly say farewell: getting blind drunk together as a last hurrah.

Indeed, though their friendship is ostensibly one that exists because Rick pays Cliff for his services, Tarantino has taken care up to this point to highlight the genuine care each has for the other. On day two, when Rick invites Cliff to watch an episode of TV he guest-starred in, Cliff already has a six-pack in the trunk and plans to order a pizza. They watch TV as they’ve surely done hundreds of times before, casually chatting, easily falling into a jovial rhythm. The foundation of their continued relationship beyond Bounty Law might be that Cliff provides Rick with services, but upon that framework, the two have built something real.

While one could devote a whole essay to the potential not-quite-platonic implications of Russell’s “little less than a wife” remark, the fact is that at minimum, the two men share a closeness that runs counter to the traditionally masculine, stoic, solo cowboy character that brought Rick and Cliff together in the first place. Rick was Jake because of Cliff. Letting go of his attachment to this character and learning to find a place in New Hollywood means leaving behind the other man who helped make it happen. Though neither man seems the type to linger on thoughts of masculinity or their own attachment to their closest male friend, it seems apparent that Rick’s employment of Cliff was less about the actual service and more about using that service as an excuse to keep his friend around as much as possible.

When the two of them touch back down in Los Angeles on August 8, 1969, extratextual knowledge tells us that this date means one thing for Sharon Tate. But within the film, following characters who have no idea about the tragedy about to befall the young actress, there’s a different sort of preemptive mourning taking place. The friendship that has sustained Rick and Cliff for the 1960s has come to its end.

The duo indeed has “a good old fashioned drunk,” but the night doesn’t wind down according to plan. In the film’s third act, an incredibly inebriated Rick taunts the Manson family and they make a last-minute decision to invade Rick’s home rather than the Tate-Polanski residence. As critic Travis Woods has expanded on in an essay for Bright Wall/Dark Room, the film’s climax follows the structure of a stunt: an actor begins the inciting action, a stunt double steps in to film the brunt of the action, and the actor comes back for the final moment and the closeup. For a character to complete such a stunt, it requires two people, one who does the dangerous work and one who gets the glory.

When Rick taunts the would-be killer hippies, he performs the inciting action. He then steps away. When they break into the house, they are met with Cliff, stuntman extraordinaire, who inflicts an assaultive (and because this is a Tarantino movie, an exhilarating) amount of brutality on the infamous family members. Then, for the pièce de résistance, Rick is called on to finish the job with a flamethrower.

This sequence bookends the film’s opening moments which show a montage of clips from Bounty Law, including a sequence in which another character asks Jake Cahill if he ever brings his bounty in alive. The TV cowboy replies “Not when there’s three of them and one of me.” Of course, there is no one Jake Cahill, there are two men necessary to bring the fantasy of the character to life. In the film’s climactic moments, where the two halves of Jake do indeed take down the threewould-be killers, Cliff and Rick come together to fulfill what they had only ever before done in a fictional context.

For Cliff, the stunt double role comes with its fair share of danger, and he does indeed take the brunt of the damage. He ends up being wheeled into an ambulance, in acid-induced high spirits. Rick, on the other hand, is a bit shook up, but relatively fine. Despite intending for this to be the last hurrah with Cliff, the final words shared between the two imply that this isn’t the end for them.

On the other side of Rick’s property fence, there’s another end that never came to pass. In Tarantino’s revisionist imagining of August 9, 1969, Sharon and the other residents of 10050 Cielo Drive lived. They were saved without ever knowing they were in danger. Sharon, the beating heart of the film, the promise of growth and development in Hollywood, the stunning, effervescent soon-to-be mother was left unscathed. She was left free to live the life we see her live in the film, one where she runs errands and dines with friends and continues to hone her craft as a performer. It is a life of day-to-day activities, beautiful and mundane experiences that we as an audience can only truly appreciate when we know this is what was robbed from her.

As the last few moments flicker on the screen — the final minutes where the fantasy of Sharon’s life being undistributed is allowed to play out — Rick achieves something special. The gates of the Tate-Polanski home open and he is welcomed into the fold, greeted by the young inheritors of Hollywood, those who thrive in the new world that Rick so desperately wants to adapt to. Rick has a place here.

The basic idea of what a stunt double does is what brought Rick and Cliff together. They each played a part of a character and this brought Jake Cahill to the small screen for several seasons. But in 1969, Bounty Law is over, and the two have to face down their changing industry without a clear understanding of what they can do for one another. Rick can only keep Cliff employed so long, and Cliff can only continue to work as a stuntman if there are stunts to be done.

Though the two still have differences — Rick enters the gates while the injured Cliff heads to the hospital, the stuntman once again doing the lion’s share of the labor — they were both necessary. When Rick walks up the driveway in the final shot, he does so by himself, but he is not a man alone.

In Tarantino’s bittersweet imagining of that fateful night in August, there is no end but rather a beginning. Though it’s not certain what the future holds for Rick and Cliff, it is clear that there is a future, or rather, many futures, futures that wouldn’t exist had the two performers not come together, each intuitively taking over their part of the role, to accomplish the real and needful stunt.

Layered Butter is a community dedicated to the art inspired by film. Through essays, interviews, and artwork, our mission is to celebrate and champion what we love about the movies. If you like our work, please considering subscribing to our Patreon, purchasing a digital issue, or pre-ordering a physical issue through our store. With your help, we'll be able to grow this community and support the artists and writers who make Layered Butter possible.